As seen on Burlington Free Press, digital and print, platforms

Parent Child Center of NCSS Early Intervention team members for Chittenden, Franklin and Grand Isle Counties share their views.

More Vermont babies, toddlers are getting help learning to talk – what was COVID’s role?

Burlington Free Press

Wearing a clear face mask, Megan Seidner got down on her toddler client’s level and began talking to them, but the child was immediately afraid. Fear reactions have become common that Seidner, until recently, hadn’t experienced in 20 years of providing speech therapy to children identified with a speech delay. “That was so jarring, at first I couldn’t figure it out,” she said. “Then I realized the littles weren’t seeing their child care teacher’s mouth.” For most of their lives, these children — those born during or just before a global pandemic — had only seen caregivers outside the home wear facemasks over the part of their face that did the talking.

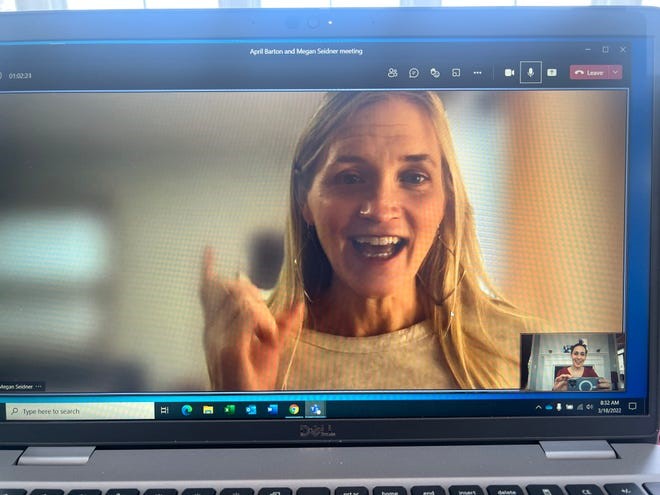

Watching mouth movements and imitation are key skills babies and toddlers use to develop speech. So, Seidner had to get basic as can be. “I had to introduce my mouth,” she said. Face masks are just one of many factors that may have contributed to a rise in speech delays among young Vermonters, a trend that was escalating before COVID-19 but had a sharp increase due a “perfect storm” of influences during the last couple years, according to Seidner. Vermont speech language pathologists report hefty case loads, dozens of kids on waiting lists. Group visits and virtual sessions — though not ideal — are necessary to reach as many children as possible with speech services. Meanwhile, Vermont’s youngest are taking longer to utter those first words and sentences, which can leave them frustrated at being unable to get their needs met and could create additional developmental delays down the line.

What is a speech delay

For at least the last decade in Vermont and nationally, early interventionists have reported an increased need for speech services for children not hitting talking milestones. Historically, typical child development has meant saying a few words around the age of one with a vocabulary of 50 words by age two. However, not hitting these numbers doesn’t automatically signal a speech delay as children develop at their own pace. A non-talking two-year-old may be referred by their pediatrician to state early intervention services for an evaluation. Depending upon the results, a child may be recommended to receive speech language support.

Delayed speech can be an early sign of autism, and can be present in children with down syndrome or cerebral palsy; or, it can be a response by children who are getting their needs met without having to communicate verbally; or a child who is focused on other skills that will show rapid progress in that area later. Identifying these children early and getting them support, no matter which group they fall into, can help minimize their frustration and accelerate progress toward developing communication as well as other skills. “A lot of kids are not talking,” Seidner remarked in late-March. “They don’t understand their role as a communicator.” Many children have not developed the foundations of language which are based on imitation, reciprocity, motor movements and gestures, she said. Seidner helps guide young children and parents weave back in those skills that may have been skipped. “It’s hard to fill in if they are two and a half and are really good at getting needs met in other ways,” she said.

Speech delays: what numbers show and therapists see

Early childhood educators, speech therapists and early intervention service networks in Vermont say they have seen an escalation in the number of children needing speech services, especially in the last year. Parsing whether speech delays are on the rise or if referrals to services are on the rise because we’ve gotten better at early identification can be difficult, according to Amy Johnson, director of the Parent Child Center which coordinates early intervention services for much of the state, including Chittenden County. Early intervention encompasses eight types of developmental delays, but Johnson said a high percentage of those receiving services of any kind need speech language support. A report from six months ago showed the amount to be 67%, she said.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, demand for human services have surged with providers seeing big case loads, waiting lists and children with complex needs across the board, Johnson said. Some regions of Vermont do not have a speech pathologist. In late March, the Parent Child Center had 43 children on a waitlist for speech services in Chittenden County. Nikki Noel, the team leader for the Franklin-Grand Isle Early Intervention team said when she started 16 years ago, one or two speech language pathologists was sufficient for Franklin County. Now they’re up to four but could really use eight providers, which she said speaks to the increased need over time.

Noel said she saw a large drop off in referrals in 2020 — a time many health and wellness visits declined due to limiting exposure during the COVID-19 pandemic — but referrals picked up in 2021 and even more in 2022. Data from the Vermont Department for Children and Families, which tracks the number of children receiving early intervention services in the state, showed a steady increase in speech services between 2017 and 2019 and the expected drop off in 2020. The 2021 numbers, however, were lower than the pre-pandemic levels in most areas, except for Bennington which continued to show an increase throughout the pandemic. The agency said the numbers representing the latter half of 2021 could still be adjusted, and provided no data for 2022 saying it was “too unreliable given standard data cleaning processes.”

What is contributing to speech delays

Seidner said she has seen more delays among children during the pandemic and suspects many causes. Masks and increased screen time were factors but needed to happen given what the community was collectively experiencing, she said. Community resources and play groups understandably dropped off and caregivers were finding their own ways to cope with the stresses created by COVID. These factors combined to create a “perfect storm” that resulted in an interruption of normal speech development for children, Seidner said.

People wearing masks meant that babies missed much of the social information that had to be relayed through the eyes only, she said. Without seeing the mechanics of how the mouth moves, imitation might not happen, which is one of the earliest skills a child acquires on their way to talking.

Passive screen use, which doesn’t require back-and-forth reciprocal communication, can fail to teach children the necessity of expression. Without play groups, library visits or playground time, parents may not have had a way to measure their children’s progress against others of a similar age to identify areas where they may have been falling behind. With the added stress brought by coping with the pandemic, parents were doing a lot of accommodating, Seidner said. An example of this would be a child who wants something stamping their foot and a caregiver giving them what they want without the child asking for it verbally, or, anticipating a child’s need and providing it before they ask.

Peek-a-boo to promote speech development

It really does take a village to see to the healthy development of children, according to Seidner, who challenges the community to get back to engaging with babies and young children. “I think about the baby in the grocery cart and no one is talking to them — such a rich social experience for them,” she said. With COVID-19, people haven’t engaged with strangers, including babies, for fear of spreading the virus. Masks have made us feel unable to fully express ourselves. Seidner encourages people to go back to sticking your tongue out at that baby in public, make faces, blow raspberries, play peek-a-boo and imitate what babies are doing back at them to teach them them their actions, expressions and sounds elicit a response.

For older babies and toddlers, encourage them to use their words to ask for something and tell you what they need. “A lot of language is learned through periods of frustration,” Seidner said. She suggested offering a choice, engaging in turn-taking or handing the child food in a container they won’t be able to open so they will need to ask for your help. Meal times can have some of the richest exchanges, Seidner said. There are lots of opportunities to ask questions and talk about food. More recently she has seen child care centers playing audio stories for children during snack time and said that can be a missed opportunity. Much of the early intervention services Seidner and her peers provide include coaching parents on these strategies. Noel said that became increasingly important during the pandemic when a provider may not have been able to offer one-on-one services with the child as often. “Those families took on that role and saw progress,” she said.

Speech service capacity is getting critical

In February, the CDC and the American Academy of Pediatrics adjusted the speech milestones for children to expect a two year old to be able to say two words in succession, like “more milk.” Before, they were expected to have 50 words in their vocabulary. Seidner is concerned this change could delay some children getting support, which is especially crucial those first three years. Johnson said fortunately in Vermont the qualifications for receiving early intervention services are very broad.

Liz Fleury, the team leader for Parent Child Center’s Chittenden County early intervention team, said capacity issues are of great concern. The state needs more investment and more workers to meet the needs of these children, who embody the future of Vermont. “Early intervention is critical for some of these children who deserve and have the right to be able to access services that will give them an equitable start to the rest of their peers,” she said.

Parents: don’t get discouraged

Seidner cautioned parents not to get down on themselves if their child needs support or felt they weren’t the perfect model during this unprecedented time of upheaval. Parents were trying to work from home and parent children at the same time, Noel said. “We were all doing the best we can.”

Johnson said to recognize how resilient children and families have been and how much they’ve achieved — that should be celebrated. Don’t get discouraged and be kind to yourself, Seidner said. Surviving a pandemic is an enormous feat, and it isn’t too late to make progress. “There’s a lot we can do to help shape our little communicators,” she said.

Contact reporter April Barton at abarton@freepressmedia.com or 802-660-1854. Follow her on Twitter @aprildbarton.

Skip to Content

Skip to Content

Comments: